Is ‘Acceptable’ Really Acceptable?

Two years later, the effects COVID-19 are still evident in public schools.

Share this story

NOTE: All rating/proficiency information in this article can be found at https://www.iaschoolperformance.gov/.

Public school ratings have been consistently dropping across the state following the pandemic, Waukee and other suburban schools included. For the past four years, the Iowa Department of Education has provided comprehensive ratings to public schools around the state with the Iowa High School Performance Profiles (IHSPPs). These ratings/statistics examine several areas of public schools; for example, racial/economic diversity, subject proficiency, and student progress.

While the Department of Education collects an abundance of valuable statistics, they don’t explain how the numbers impact students; WHS Principal Cary Justmann highlighted their implications for our school. “I would say it doesn’t affect the work behind the scenes at all,” said Mr. Justmann. “We’re not happy with an ‘acceptable’ score, but we know coming here every day we’re doing better than that.” To most parents/media sources, ‘acceptable’ has the negative connotation of ‘low-performing,’ but the situation is improving behind the scenes. “My thought is, what does ‘commendable’ mean to ‘acceptable?’” said Mr. Justmann. “It means a lot in the newspaper and it means a lot to our parents for five minutes, but I think the work we do for 180 days is probably more lasting.”

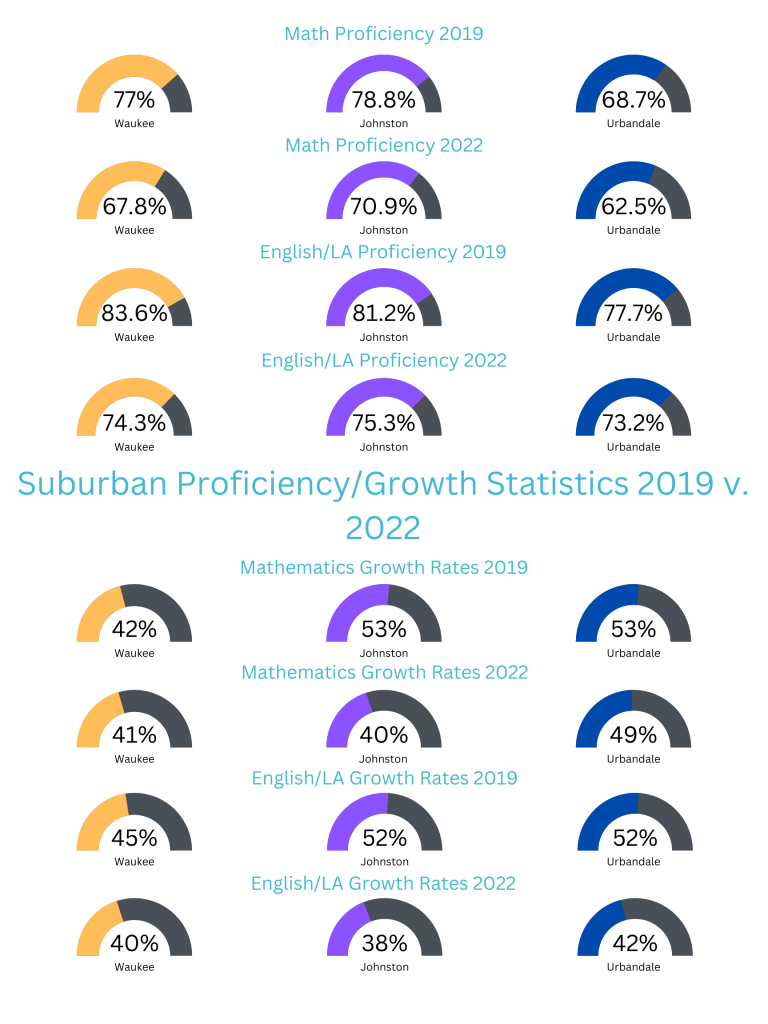

The IHSPPs rating system provides each public school in Iowa with a score between one and one hundred, with the average rating in 2022 being 54.65/100 compared to 54.94/100 in 2019. Ratings divide each school into one of six subgroups: Exceptional (66.31 and above), High Performing (60.61-66.30), Commendable (54.91-60.60), Acceptable (49.21-54.90), Needs Improvement (44.17-49.20), or Priority (44.16 and below). Each school’s rating is a compilation of proficiency scores, growth rates, ELP composite, and more. See the provided infographic for specific statistics regarding subscores. Our school’s rating sits at 53.56 in 2022, putting us in the ‘acceptable’ category. ‘Acceptable’ is commonly viewed as a negative score in local media and among parents, but it shouldn’t be viewed as such. Other suburban schools have performed similarly: Northwest is 54.34, Johnston is 54.54, and Urbandale is 52.62. Pre-COVID statistics suggest that the pandemic may have contributed to lower ratings. For example, our 2019 rating was 56.53; in comparison, Johnston was rated 59.05, and Urbandale was rated 56.77, with Northwest not yet existing. Each school was achieving within the ‘commendable’ range, a more positively-viewed rating.

‘Commendable’ was the standard for suburban schools three years ago; however, the expectation has carried through a pandemic in which we lost nine weeks of in-person education and had students learning online for months. “We’re still getting our feet under us, which I think is why the suburban areas have seen a bit of a dip,” said Mr. Justmann on recovering from lost learning. “I do think we can do better. I always think we can do better.” Along with every other suburban school, we are still bouncing back. Normalcy will return in time. As someone who learned online from March 2020 to January 2021, I’ve begun to feel the effects less and less, and school is becoming more comfortable; however, during the pandemic, I was lost. I knew my teachers were doing their best, but the challenge just wasn’t there. I wasn’t engaged, which led to a substantial dip in my and so many others’ ISASP scores.

Suburban schools like Waukee have seen drops in ratings; however, city schools’ ratings have taken a much harder hit. For example, Roosevelt High School slipped from 51.56/100 in 2019 to 42.98 in 2022. Roosevelt’s score decline is similar to every inner-city school. Why were they affected so disproportionately? According to the Des Moines Register, as many as 7,500 homes within Des Moines Public Schools were without internet when COVID-19 was at its peak, making online learning nearly impossible. Thousands of kids struggled to access their education. Sophomore Catelyn Mead attended Meredith Middle School in Des Moines during the pandemic. “It was difficult to get computers to everyone, for everyone to have internet access, and to have people really participate in the class,” said Mead. “I think it placed a lot of stress on teachers, students, and parents.” In predominantly affluent districts like Waukee, we tend to ignore the fact that we’re lucky. Most school districts do not have access to the resources that we have. But a lack of resources wasn’t the only factor impacting kids in city districts like Des Moines. Senior Cyd Irvine attended Roosevelt High School during the pandemic. “Roosevelt is a very tight-knit community with a lot of students who do not have support systems at home,” said Irvine. “When COVID caused schools to shut down you could almost feel those people suffering because they were unable to go to the place where they could feel wanted.”

Waukee has seen a dip in scores, but schools that serve lower-income areas fare much worse and face the possibility of losing funding to a proposed voucher program.

The private school voucher program is a controversial piece of legislation backed by Governor Kim Reynolds and several state House/Senate Republicans. The program would give families the option to pull their children from public schools through taxpayer-funded scholarships. While supporters claim vouchers will help disadvantaged families, critics argue that the voucher system will both decrease public school funds and ignore the schools that are hurting post-COVID. For schools like Waukee, vouchers would be largely irrelevant. The transition back to normalcy has not been difficult, and we’re getting back on track; however, for schools like Roosevelt and Marshalltown, the transition has been a nightmare. They require external help that they aren’t receiving, and could now have a funding cut due to the voucher program.

Apart from vouchers’ implications on schools, questions have arisen about their constitutionality. 84% of Iowan private schools are religiously-affiliated; for this reason, state-sanctioned scholarships may violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment (no laws respecting religious establishment). Regardless of their constitutionality, vouchers will be problematic for education in the state of Iowa. Presently, they have not passed through the state legislature due to rural Republican representatives’ concerns about areas with minimal private school options. Due to Governor Reynolds’ campaigning against such leaders, many of them have since been unseated, giving way to the passage of a voucher bill during the next legislative session in January. Leaders on both sides of the legislature must come together to form a bipartisan piece of legislation that will not have detrimental effects on our public schools.

A rating of ‘acceptable’ may seem negative to our parents and the media, but many of our local neighbors are having a much harder time. Our state government must come together to find a logical, nonpartisan solution to the problem.