A Trip to the Jordan House

A deep look into the life of James Jordan, Underground Railroad in Iowa

Share this story

Co-written by Mays Al Sharqi (Senior)

Mays:

The bus hummed, and the familiar smells of gasoline and leather imbued the air. As we rode to the Jordan House, we drove past acres of rumpled prairie grass and land for sale. The history of the European settler movement in the U.S. shrouds my view. The bus glides past a graveyard scattered with reflective obsidian tombstones.

The bus rocked on a rugged gravel road, wrapping around the wooden house and leading us to the entrance. The house was a small, intricate Victorian home, decked with Christmas wreaths and bows.

Fatimah:

The gray sky glistened as we arrived. The bare and twisted black trees framed the home as we walked up the dirt road and entered.

Mays:

The class stepped into a cramped wooden room that smelled of dust and history. Framed black and white photos hung on the walls; to the left was James Jordan, the owner of the home, and his wife. Ahead was a photo of three black women working a field.

Fatimah:

Our tour guide spoke first about the paintings on the walls and the great lengths it took to maintain the carpeted floors of the formal parlor. She introduced James Jordan, a very religious settler who made his home in Iowa. He was “a businessman and legislator,” our guide said, he had a large family and was married twice.

This tour, provided for by the West Des Moines Historical Society, began showcasing James Jordan’s house as a historical museum after citizens listed it as a national landmark. The goal is to provide historical context to the life and legacy of Jordan and his family.

The fact that he was an abolitionist whose home was a stop for the Underground Railroad was mentioned later in the tour.

Mays:

The tour begins in one room over, with a long-winded description of the carpet-making process. I was taken aback by this, as we were in a home that was part of a monumental moment in African-American history. The guide spoke mostly of the family’s life and activities, including their parties and domestic practices.

We re-entered the room with the photographs, where she was avoidant of the photo of the women in the field. My partner Fatimah raised her hand to question this inaction; She asked about the significance of the photo, which was to the guide’s right. She looked over as if she had just seen it, stating that it was, “a print from this time period,” and that she did not know what the photo meant. I found this curious, as the photo stuck out to me the moment I stepped into the room.

Fatimah:

As we moved from the foyer to the study, I noticed a cardboard cutout depicting a black woman who had escaped from slavery. There was a piece of paper taped to it, with a description including her life and her emancipation. Our guide later commented that these cutouts which were scattered about the house were donated by a high school student to commemorate female abolitionists. This high school project addressed the abolitionist movement more than the tour itself.

Mays:

We proceeded into the kitchen, where she spoke about clothing irons and other appliances at length. As we proceeded to the dining room, we saw a small sliding divider out of which food would be served and picked up by the people in the room; could this have been for some kind of servant? The guide, again, does not address this detail.

Jordan was a congressman and abolitionist, which was introduced when we were guided into the office. The room was furnished with wooden chairs ornamented with the horns of the animals he hunted for sport. An original print of Abraham Lincoln stared down at us with a firm gaze, hung above a shotgun gifted to Jordan by his colleague John Brown.

We finally got to the basement, where the freedom seekers were hidden.

Fatimah:

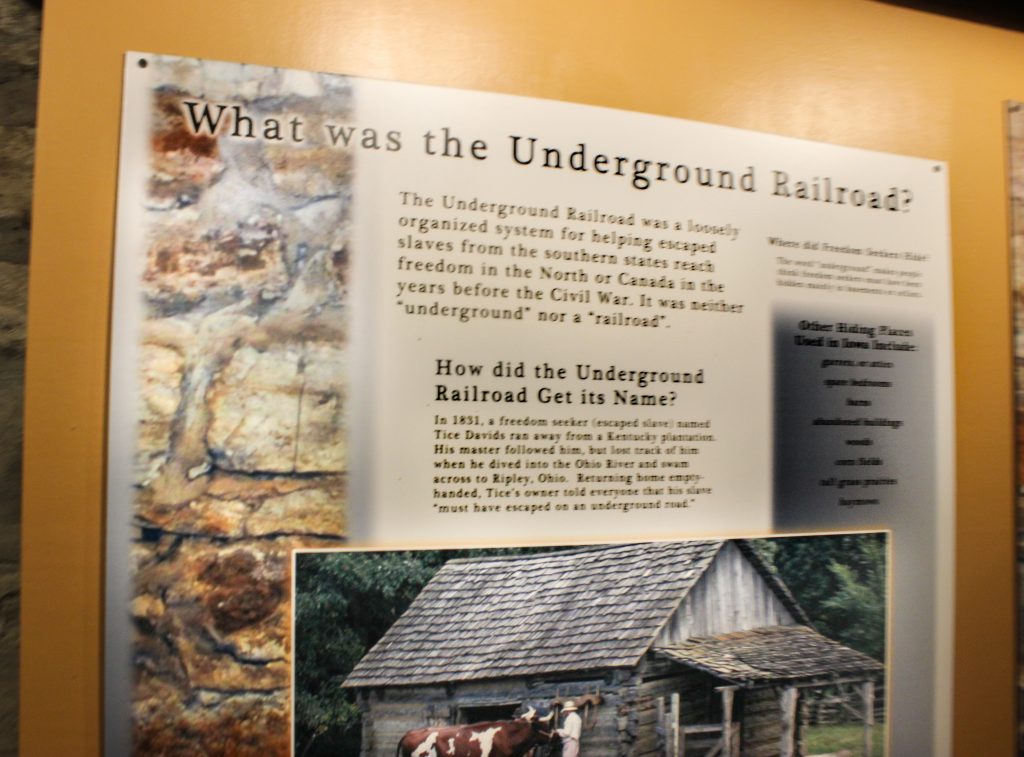

The basement was separated into two rooms, both made of stone. The first was the temporary living quarters that the family used while the rest of the house was being built, which included a furnace and animal hides on the walls. The second area seemed to have been created later in order to acknowledge the Underground Railroad.

Mays:

Dust coated my lungs as I tried to place myself back in back in time. I could not do this, however, as the guide did not discuss the experiences of slaves that were in the basement. I felt myself in an unassuming, cramped room when I was expecting to be overcome with introspection, with the weight of the emotional events on my shoulders.

Fatimah:

During our brief moments in the separate room, our guide spoke about John Brown as “one of the guides that were taking freedom seekers through different paths throughout the United States.” She said that Brown believed that slavery should be ended “by any means necessary,” and spoke about how he had planned a raid on Harper’s Ferry that resulted in his execution. She said that John gave James a rifle on that last raid.

Mays:

The tour guide didn’t know anything about the people who passed through this room, but instead spoke briefly about the famous Henry “Box” Brown, a formerly enslaved man who hid in a wooden box for 26 hours, transported on trains, to escape the horrors of captivity. She claimed that after this grueling railroad trip, Brown, “Came out of the box dancing and singing.”

She moved on and spent much more time talking about the white abolitionist John Brown. The tour simply continued, with no mention of slavery brought up again.

Fatimah:

The experience posed many questions.

Why speak about John Brown and only mention one detail that connects him with James Jordan?

What did Jordan do to help escaped slaves? Why is his role not mentioned very much at all during this tour?

What does “Henry’s Freedom Box” have anything to do with The Jordan House?

I conducted some research to answer these questions:

According to the West Des Moines Historical Society, James Jordan was known as the “Chief Conductor for the Underground Railroad in Polk County.” Freedom seekers were said to have hidden in various areas around the Jordan property. Regarding John Brown, the historical society says that he merely stayed “at least twice,” at the house. In addition to his contributions to the Underground Railroad, James Jordan also organized the State Bank of Des Moines, was elected to both the Senate and the House, and led the cause to move the state capital from Iowa City to Des Moines.

Henry’s Freedom Box is a book based on a true story, depicting an enslaved man separated from his wife and children, who later mails himself to freedom. The story is said to be related to the Underground Railroad, giving additional context for the Underground Railroad portion of the tour.

Holding the Underground Railroad portion of the tour underground may have been convenient for the historical society, however, it poses some inaccuracies by perpetuating the idea that the Underground Railroad was actually underground. In reality, the freedom seekers were said to have been hidden in the exterior areas (“fields, barns and outbuildings on the property,” according to the West Des Moines Historical Society) and not in the basement of the building.

During the tour, the main context we received was about the material details of the home itself. The wash basin in the kitchen, the pictures on the walls, and the armchairs made of bones don’t give the context and educational value needed to fully comprehend the history. It would be acceptable for the tour to focus solely on the material situation if it were an ordinary Victorian house, but this is the Jordan House; it is important for the history told to be diverse and rich, depicting not only the material conditions, but the legacy of the family who lived within it, and the freedom seekers who called it a safe haven.